Destruction of Empire #4: Polybius—When Empires Get Too Powerful and Too Rich for Their Own Good (Greece/Rome)

The “Destruction of Empire” blog series explores why nations collapse, based on warnings from history.

You can read all the individual articles here.

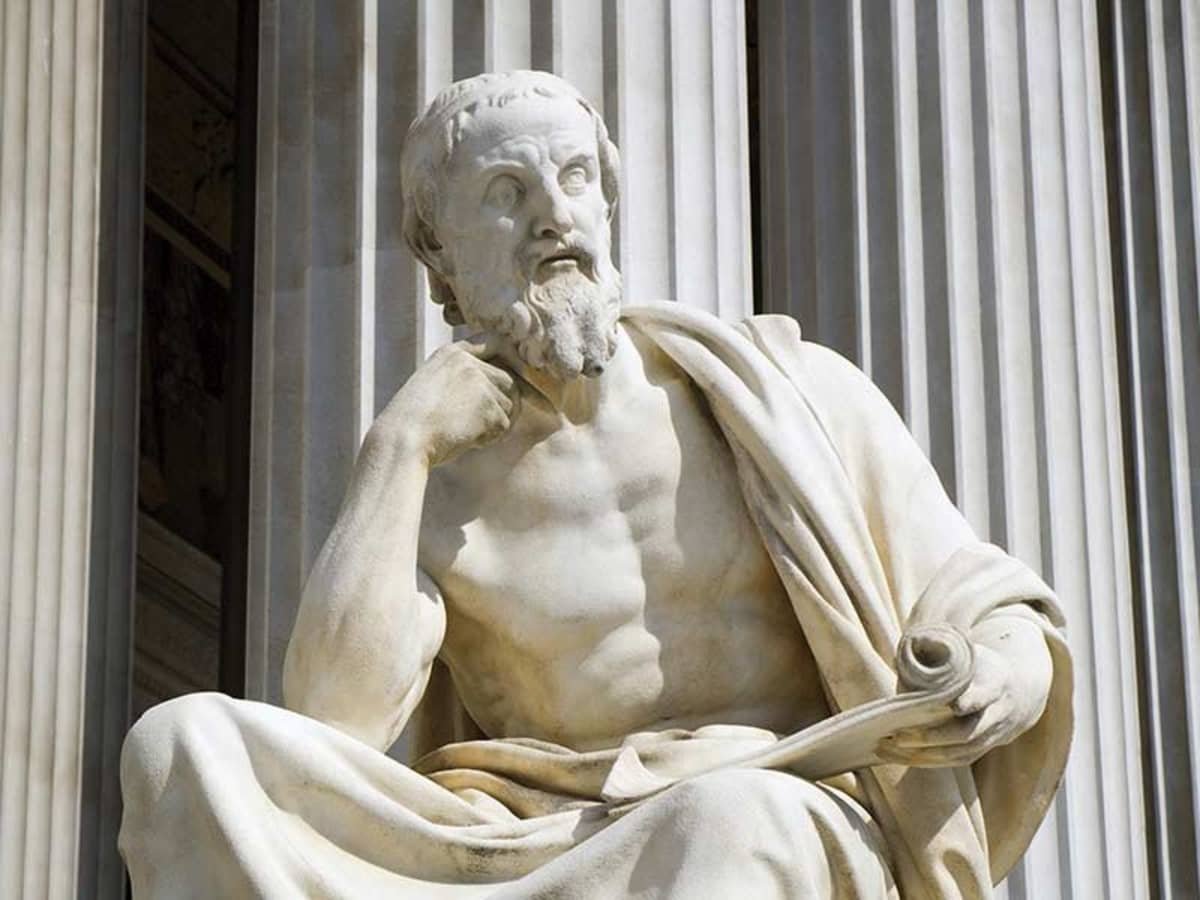

Polybius

Polybius was a Greek statesman and historian living in the 2nd century BC, when the Roman Republic had risen to prominence, and exercised a great degree of control over Grecian affairs. After the Romans defeated Perseus of Macedonia in 168 BC, Polybius was among approximately a thousand prominent Greeks who were deported to Rome without trial.

While in Rome, he became friends with Scipio Africanus, the Roman general famous for his exploits in Spain, and especially against Carthage in the Third Punic War. Polybius became his mentor, enabled him to remain in Rome. He was at Scipio’s side when he besieged Carthage in 146 BC.

His most famous work, The Histories, originally consisted of forty books. Unfortunately, only Books 1-5 remain in their entirety, with fragments of the other books (particularly Books 6 and 12) remaining as well.

The purpose of The Histories was to narrate the rise of the Roman Republic, and examine the causes of its success. Polybius’ analysis of the Roman constitution—especially its division of powers between the consuls (executive), the patricians (aristocracy), and the plebians (the people)—played an immense role western political thought, especially among the American Founders, who looked to the Roman Republic as a model for emulation and warning.

Polybius explained the purpose of his work in §§1-2 of Book 1 of The Histories (pgs. 3-4 in the work cited below):

(§1) If earlier historians had failed to eulogize history itself, it would, I suppose, be up to me to begin by encouraging everyone to occupy himself in an open-minded way with works like this one, on the grounds that there is no better corrective of human behavior than knowledge of past events. But in fact it is hardly an exaggeration to say that all of my predecessors (not just a few) have made this central to their work (not just a side issue), by claiming not only that there is no more authentic way to prepare and train oneself for political life than by studying history, but also that there is no more comprehensible and comprehensive teacher of the ability to endure with courage the vicissitudes of Fortune than a record of others’ catastrophes.

Obviously, then, the general principle that no one should feel obliged to repeat what has often been well said before is particularly pertinent in my case. For the extraordinary nature of the events I decided to write about is in itself enough to interest everyone, young or old, in my work, and make them want to read it. After all, is there anyone on earth who is so narrow-minded or uninquisitive that he could fail to want to know how and thanks to what kind of political system almost the entire known world was conquered and brought under a single empire, the empire of the Romans, in less than fifty-three years—an unprecedented event? Or again, is there anyone who is so passionately attached to some other marvel or matter that he could consider it more important than knowing this?

(§2) The extraordinary and spectacular nature of the subject I propose to consider would become particularly evident if we were to compare and contrast the most famous empires of the past—the ones that have earned the most attention from writers—with the supremacy of the Romans…The Romans, however, have made themselves masters of almost the entire known world, not just some bits of it, and have left such a colossal empire that no one alive today can resist it and no one in the future will be able to overcome it. My work will make it possible to understand more clearly how the empire was gained, and no reader will be left in doubt about the many important benefits to be gained from reading political history.

In Book 6, Polybius offered a brief but penetrating prediction of what was in store for Rome now that it was supreme. In short, he believed that once any state became powerful enough to ward off all external threats (as he saw Rome had achieved), it was likely to experience a period of peace and prosperity that would lead to extravagant luxury. This, in turn, would encourage political gamesmanship and “democratic” revolutions.

Ironically, after the civil wars of the 1st century BC, Augustus would become the first emperor of what history now recognizes as the Roman Empire. But he did so by never assuming such a title to himself, while claiming to restore “the republic” in the name of the people.

In short, Polybius’ prediction was accurate—a fact that makes his observations as relevant today as they were when originally written nearly 2,200 years ago.

Polybius, The Histories (Book 6, §57)

Source: Polybius, The Histories (Book 6, §57); Polybius, Robin Waterfield, trans., Polybius: The Histories (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 411-12.

(§57) I hardly need to argue that every existing thing is subject to decay and decline: the inescapable facts of nature are convincing in themselves. Where states are concerned, there are two kinds of natural agent that may be responsible for their decline, one external, the other innate. External agencies are too indeterminate to be studied with any certainty, but internal decline is capable of orderly study. I have already stated the sequence in which the various constitutions develop and how they change into one another, and anyone who is capable of drawing conclusions from premises should by now be in a position to predict the future.

I think there can be no doubt what lies in the future for Rome. When a state has warded off many serious threats, and has come to attain undisputed supremacy and sovereignty, it is easy to see that, after a long period of settled prosperity, lifestyles become more extravagant, and rivalry over political positions and other such projects becomes fiercer than it should be. If these processes continue for very long, society will change for the worse. The causes of the deterioration will be lust for power combined with contempt for political obscurity, and personal ostentation and extravagance. It will be called a democratic revolution, however, because the time will come when the people will feel abused by some politicians’ self-seeking ambition, and will have been flattered into vain hopes by others’ lust for power. Under these circumstances, all their decisions will be motivated by anger and passion, and they will no longer be content to be subject or even equal to those in power. When this happens, the new constitution will be described in the most attractive terms, as ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy,’ but in fact it will be the worst of all constitutions, mob-rule.