Destruction of Empire #1: Livy—The Importance of Studying History, and the Perils of Hedonism (Rome)

Making Wisdom Popular

The “Destruction of Empire” blog series explores why nations collapse, based on warnings from history.

You can read all the individual articles here.

Thomas Cole, Course of Empire: Destruction (1836)

The first installment in the Destruction of Empire series comes from the ancient Roman historian, Livy. Born in the waning days of the Roman Republic, he died somewhere around either the end of the reign of Rome’s first Emperor, Caesar Augustus, or the beginning of the reign of its second, Tiberius. His life therefore encompassed one of the most transformative periods in the history of Rome. Much of his monumental History of Rome (sometimes referred to as Ab Urbe Condita, or “From the Founding of the City”), 142 books in total, has been lost to history. But large portions of it remain (around 35 books), representing the single largest history from the time period. Livy was widely read by the Founding Fathers, and was the subject of Machiavelli’s famous Discourses on Livy.

In the opening lines of the first book of his history, Livy makes clear that he believes the Roman Republic fell into the despotism of the Roman Empire because of moral decline. For him, the study of history is essential to understanding this decline, and drawing the appropriate lessons[1]:

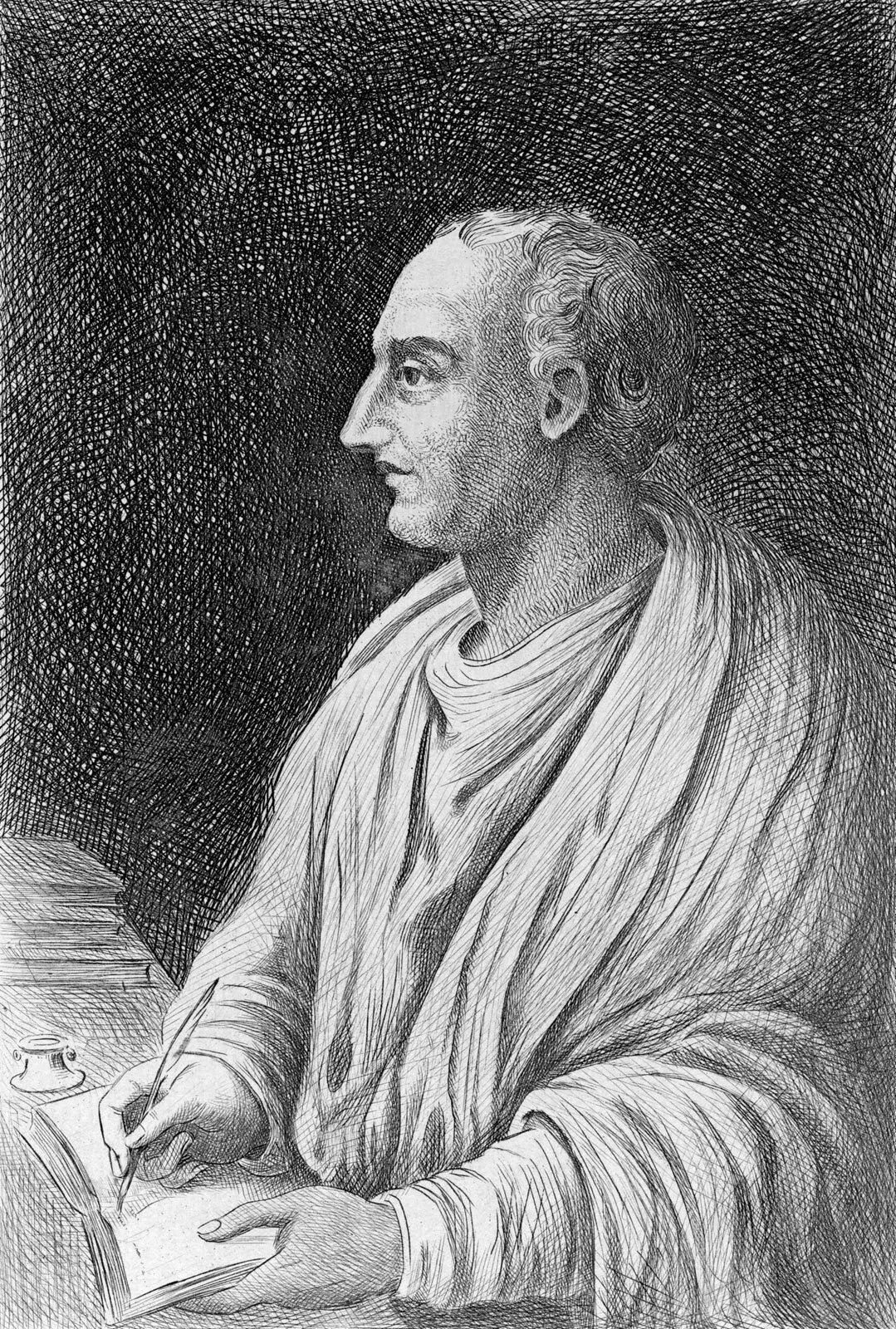

Titus Livius (59/64 BC-AD 12/17)

I invite the reader’s attention to the much more serious consideration of the kind of lives our ancestors lived, of who were the men, and what the means both in politics and war by which Rome’s power was first acquired and subsequently expanded; I would then have him trace the process of moral decline, to watch, first, the sinking of the foundations of morality as the old teaching was allowed to lapse, then the rapidly increasing disintegration, then the final collapse of the whole edifice, and the dark dawning of our modern day when we can neither endure our vices nor face the remedies needed to cure them. The study of history is the best medicine for a sick mind; for in history you have a record of the infinite variety of human experience plainly set out for all to see; and in that record you can find for yourself and your country both examples and warnings; fine things to take as models, base things, rotten through and through, to avoid.

Livy makes clear that his criticism of the moral decline of his country is in no way incompatible with genuine patriotism—in fact, that is its source. He also touches on what he sees as one of the greatest dangers to any society—luxury, and the hedonistic culture that results:

I hope my passion for Rome’s past has not impaired my judgment; for I do honestly believe that no country has ever been greater or purer than ours or richer in good citizens and noble deeds; none has been free for so many generations from the vices of avarice and luxury; nowhere have thrift and plain living been for so long held in such esteem. Indeed, poverty, with us, went hand in hand with contentment. Of late years wealth has made us greedy, and self-indulgence has brought us, through every form of sensual excess, to be, if I may so put it, in love with death both individual and collective.

But bitter comments of this sort are not likely to find favor, even when they have to be made.

Such are the first lessons of Livy.

FOOTNOTES

[1]Livy, History of Rome (Book I, §1); Livy Aubrey de Sélincourt, trans., The Early History of Rome: Books I-V of The History of Rome from its Foundations (New York: Penguin Books, 2002), 30.